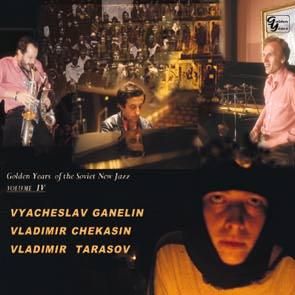

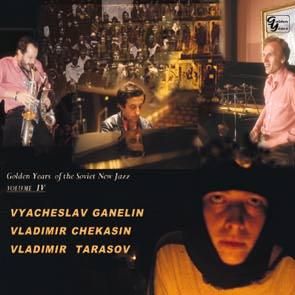

Disc 1 Vyacheslav Ganelin solo; Ganelin/Chekasin duo - 77'48

Disc 2 Tarasov/Chekasin duo; Ganelin/Tarasov duo - 77'24

Disc 3 Vladimir Chekasin Quartet; Chekasin/Vysniauskas Quintet - 60'20

Disc 4 The Ganelin Trio - 75'02

The last volume documenting golden years of the Soviet new jazz is devoted

entirely to the legendary Ganelin Trio. First three discs deal with the

musicians of the trio playing in different combinations with each other and

their own groups while disc 4 boasts two major works by the Trio. Accompanied

by a 28-page booklet, this edition will finally help re-evaluate the

significance of the Trio for the development of music inside the Iron

Curtain. It will also help finding a proper place for the Trio amongst the

best new jazz ensembles of Europe and America. Limited edition 750 copies.

I first heard the name of Ganelin in the least likely place. It was the

winter of 1976-77 and I did my obligatory year of the army service in a

remote garrison on the island of Novaya Zemlya, beyond the Polar Circle.

Information and music deprivation were amongst the most severe burdens of

the most excruciating experience and I avidly waited for every letter from

the mainland. Apart from news about family and friends I was desperate for

what was going in the world of music from which I was forcibly cut off --

there was no way of course in the Soviet army to receive new recordings or

listen to the BBC, Voice of America or Radio Liberty. Fresh out of the

University, I was still very much into rock: progressive bands like King

Crimson, Yes, and Jethro Tull carried the flag of the day. Although my jazz

initiation had begun before I was drafted -- I remember listening to Willis

Conover's Jazz Hour on Voice of America and even some jazz-rock and early

ECM on Polish radio � improvised music was still pretty much a terra

incognita. Apart from a couple of token compilations with fabulous but

totally harmless Ella and Louis on Melodia, neither I, nor any of my friends

had much jazz in our record or tape collections.

I will never forget the exhilarating shock I experienced when a like-minded

friend proudly informed me in a letter that Melodia, that bastion of

conformity, released a record compared to which King Crimson (then the

epitome of the avant-garde for us) sounded, he said in the letter, "like a

nursery rhyme". The record he had in mind was Con Anima -- the Ganelin trio's

first official release. Outside major capitals where I lived then, the

record, although officially published, proved not any easier to find than

any Western rarity. With a great effort, upon my return home after the army

service, I could find only a copy in a "blind" cover -- no cover art, no

names of the musicians, no instrumentation listed.

Nevertheless, it was a window into a new world. To find the door I had to

move to Leningrad, and finally, in October 1978, at the concerts of the very

first Autumn Rhythms festival, I saw the trio live for the first time. Along

with my other great discoveries of those few days: Anatoly Vapirov with then

very young Sergey Kuryokhin and Arkhangelsk --

the trio stood out among the otherwise rather plain derivative mainstream.

Of course, I soon found Con Anima in a proper sleeve with supremacist red

triangle and the names that looked weird with their funny and totally

inappropriate Lithuanian flexions: Ganelinas, Tarasovas, Chekasinas. Of

course, they were from Vilnius in Lithuania, the westernmost corner of the

Soviet Union, the avant post of freedom and "otherness".

By the time I met them in the late 1970s the trio had reached the peak of

their creativity. I was fortunate to see them in full glory and power. The

story began, however, much earlier when in mid-sixties, Vyacheslav (Slava)

Ganelin, still a student of piano and composition at the Vilnius

conservatory, in spite of the prevailing craze for rock went into jazz. With

Bill Evans as his first strong inspiration, Ganelin played impressionistic

piano both solo and with various partners at the Neringa Cafe -- the mainstay

of Lithuanian jazz life. It was there that he met Vladimir Tarasov, then a

newcomer to Vilnius where he escaped from his hometown Arkhanglesk, far in

the Russian North. Not that there was no jazz life in Arkhangelsk: even

before leaving Tarasov had played there with Vladimir Resitsky, who later on

created Arkhangelsk -- one of the country's best jazz bands. But cosmopolitan

westernised Vilnius offered many more opportunities for the aspiring jazz

neophyte.

The two played together from 1969 to 1971. It was at that early stage that

Ganelin, equipped with a classical composer training, started giving his

programmes Italian titles which sounded -- certainly with a bit of tongue in

cheek -- like "proper" classical pieces. The first of these titles -- Opus A

Due -- was reused again in 1982 when growing frictions with Chekasin forced

Ganelin to go back to the roots of the trio, i.e. his duo with Tarasov.

Chekasin, however, at that time played feverish Charlie Parker/Ornette

Coleman inspired alto sax in his home city of Sverdlovsk (now Ekaterinburg),

thousands miles east, deep into Russia, in the Urals. He was blissfully

unaware of the duo's existence, even though they had gained some notoriety

in the jazz community having played at a number of festivals across the

country. He didn't even bother to show up at their concert when they came

to Sverdlovsk to play at the local jazz club. He was too busy that night

blowing his own horn at a dancing hall for the military, literally next door

to the club. The concert organiser, a local jazz enthusiast was, however,

eager to show the visiting guests a home-grown talent and after the concert

he brought Ganelin and Tarasov into the officers' club.

"As soon as we walked into the hall we saw a fascinating sight", --

reminiscences Tarasov in his book The Trio. "Up on the elevated stage stood

Chekasin swinging his sax and playing in Coltrane style, absolutely freely,

without even a slightest hint of rhythm. Baby-faced Ural girls in awkward

felt boots were helplessly stomping in the middle trying to find at least a

semblance of time in his wild playing. Can you imagine dancing to Coltrane?"

(Vladimir Tarasov, Trio)

A subsequent short jam left no doubts. Right there and then the decision was

made and a few weeks later Chekasin was already in Vilnius. "We had always

tried to find musicians who would share our way of thinking and our style.

Everybody we had tried before could at best be a decent accompanist, without

a trace of their own initiative. Vladimir Chekasin was the first. And the

last". (Vladimir Tarasov, Trio)

It was a remarkable symbiosis, a unity much bigger than the sum of its

parts. Ganelin: ratio, reason, structure, form and � probably not quite

consistently, but hugely importantly -- humor. Tarasov: driving force,

engine, and at the same time inexhaustible inventiveness in embellishing the

overall sound with myriads of delicate subtle sonic nuances. In other words,

much more of a percussionist than a drummer. Tellingly, it was Tarasov who

after the trio's collapse played solo more than the other two. And Chekasin:

thrust, vitality, wild unharnessed energy, emotional power multiplied by

formidable technical prowess.

For a good decade, which fortunately coincided with the trio's breakthrough

in the West, they were really awe-inspiring. Even for us who knew their

records and saw them at least once, often two or three times a year, some of

these concerts really sent shivers down the spine. And at the same time

they were full of fun, wit and even sarcasm, which, however, was never

malicious. A powerful three-headed beast, a gentle giant, who could also be

delicate, subtle and funny. Take their great encores: Mack the Knife or

Summertime -- if they played jazz classics it had to be with humour.

Each of those concerts in the late 70s and early 80s was a festival of free

spirit. Everybody you knew in town, whether it was Leningrad or Moscow,

Vilnius or Odessa, Riga or Novosibirsk, was there. And not because it was a

social occasion. With most of the arts heavily censored, improvised music by

definition bore a spirit of rebellion. Artists, writers, people of film and

theatre, just anybody capable and willing to think, flocked to those

concerts. The omnipotent regime frowned: "Should we be ahead of the West

even in the avantgarde? No, our people don't need this kind of music" -- this

utterance of the Melodia boss which delayed the release of their second LP

Concerto Grosso for three years became proverbial. Ironically -- or

understandably? -- confrontation and hostility were at times even more

acrimonious from within the jazz community. A prominent Moscow musician and

composer never referred to the trio in any other way than as musical

eccentrics and clowns.

We took incredible pride in the trio's success in the West, which, we

realized, was based first and foremost on the originality and profundity of

their music. Thanks to Western recognition they were about the only

avant-garde jazz band that were actually allowed to make it out of the

underground into official Soviet recognition. Like Andrei Tarkovsky's films

or Yuri Liubimov's Taganka theatre, they were single spots of quality and

freshness in otherwise dull socialist realism landscape of the official art.

They were also a beacon for the others to follow. Everybody else: from

Sergey Kuryokhin to Arkhangelsk, from Tri-O to Guyovoronsky and Volkov were

trailing behind, their quest made easier by pathfinders from The Ganelin

Trio. Their influence spread across the bor- ders far beyond jazz: in 1974

they played concerts with Dmitry Pokrovsky Ensemble -- the pioneers in

unearthing authentic Russian ethnic music; in 1979 they introduced the

element of performance art which Tarasov later on developed in his

performances with Ilya Kabakov and Dmitry Prigov; Chekasin was the first to

turn his performances into burlesque theatrical shows, and it was there that

Kuryokhin borrowed the basic idea for his Popular Mechanics.

But still their most enduring accomplishment is of, course, the music

itself. It is fortunately, thanks mostly to Leo Records, well documented.

Unfortunately it is not nearly as well studied and analysed. This is hardly

the place for the long overdue thorough analysis of the trio's music.

Tarasov's book, fascinating reading as it is, provides a lot of historical

facts but, alas, shies away not only from how this magnificent music was

actually being created but also from discussing extremely complex

relationships between the three individuals. These relationships produced

the vibrant, vital and tragic art, but inevitably led to the trio's collapse

in the mid 1980s.

Their paths went totally astray from each other. In the last couple of years

before the final collapse in 1987, they played together mostly out of

necessity and inertia; human interaction, unity and cohesion long gone. I

remember a very long and very sad conversation I had with Ganelin on the eve

of his departure to Israel: he just felt he could not go on like this

anymore. Now in Israel, he teaches at the conservatory, composes music,

occasionally performs and releases new recordings. Tarasov is all over the

world with countless ambitious performances in most prestigious venues. His

love of visual arts and many friendships with influential artists translated

not only into numerous commissions but encouraged him into doing his own

projects in visual arts. Russian Museum in St.Petersburg featured an

exhibition of his work in March 2003. He's the only one still in Vilnius, at

the time of this writing holding a prominent position as the General Manager

at the same theatre where Ganelin worked for many years before emigration.

Chekasin is like a travelling band, now in Moscow, then in Vilnius, then in

Odessa, then in Germany, staging extravagant shows with dance, brass bands

and what not.

If you want my opinion, not one of them could match in their separate work

the level of music the trio produced.

For years the breakup seemed to be totally irreversible. Two years after

Ganelin emigrated, in 1989, all three were at Soviet Avant Jazz Festvial in

Zurich. Even the idea of playing together was unmentionable.

With years old acrimonies faded away. In October 2002, at the Frankfurt Book

Fair the trio played together for the first time in 15 years. All the

ingredients of the former Ganelin Trio were there, as if this 15-year gap

did not happen. But the much anticipated reunion turned out to be more of a

warm up. At the time these notes are being written it is still unclear

whether it was a one off event or a beginning of a comeback.

Alexander Kan,

London, April 2003.