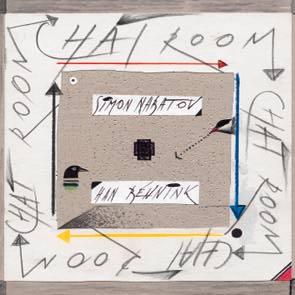

Extraordinary meeting of two giants of the contemporary music scene playing

to each other's strength, Nabatov being in a more playful mood than usual

while Bennink is much more restrained and disciplined. The CD was recorded

the following day after a pretty "barbaric" gig at the Stadtgarten Festival

in Koln. Both musicians are in a mellower mood. They listen to each other to

achieve a meaningful whole. Total duration 61'15.

Han Bennink's c.v. includes a lot of improvised duos, with special attention

paid to piano players: his 40-year playmate Misha Mengelberg of course, but

also Irene Schweizer, Cecil Taylor, Steve Beresford, Myra Melford, Matt Shipp,

Guus Janssen, Fred Hersch. . . a partial but impressive list. Not

that these meetings are always a pleasure for the pianist. Misha has often

endured half-hour fusillades that left anything he might play buried under

the rubble; he'd wait till Han had exhausted his ammo before digging himself

out. Duo partners who expect Han to follow their lead, in terms of tempo or

density or dynamics, find that he usually reserves such prerogatives for

himself. One pianist who'd toured with Bennink observed with despair that

he'd never repeat last night's successful tack tonight. All this is

consistent with the popular image of the drummer as Dutch free-jazz maniac,

force of nature fierce as a Waddenzee wind.

So how to explain the supremely cooperative, discreet Han Bennink heard

herein?

Some context will help. Simon Nabatov: "Around 1997 Huub van Riel started

featuring me with my different bands in a series of concerts at Amsterdam's

Bimhuis: solo, duo with Nils Wogram, trio with Drew Gress and Tom Rainey,

quartet with Wogram, Frank Gratkowski and Phil Minton, quintet with Herb

Robertson, Mark Feldman, Mark Helias and Rainey. After the gigs, hanging out

at the bar, Huub and I talked about other possible settings, and one of his

first ideas was the duo with Han. I was immediately into it, of course.

"We played together for the first time in December 1999. I remember

arriving by taxi for the soundcheck practically at the very same moment Han

showed up. 'Oh, it's a nice sign,' I thought. We set up, started playing,

and had a hookup right away. After a few minutes Han jumped up saying,

'Please, let's save it all for the evening.' So he took me out to the

musicians' bar for a dinner and a nice chat. The gig that night was real fun

and we decided we should continue. And so we did, playing some loose gigs,

doing short tours, and playing a few times in trio with Ernst Glerum on

bass.

"There are no technical difficulties whatsoever, improvising with Han,

and I've generally known him to be cooperative. Obviously, it's not his

modus operandi, but he seems to leave the anarchist partly outside of our

musical encounters. Also, this recording took place one day after our

appearance at the Stadtgarten Festival, a short and pretty 'barbaric' set,

where we both played rather aggressively and Han pulled damn near every

theatrical and musical stunt he could think of. When we recorded next day,

we were more mellow somehow -- not spent, just more concentrated on the

music -- adjusting to the contrast between the overcrowded rowdy atmosphere at

Stadtgarten and the empty but very friendly, sunny room of LOFT. All the

music was improvised, and there are no edits within pieces."

Of course there's more to it than that. The pianists cited above are all

gifted stylists, and sometimes much more, but Nabatov also has his gifts,

one being the smarts to play to Han's strengths. A comparison with Nabatov's

LOFT recording from ten months earlier, the solo Perpetuum Immobile (Leo LR

358), is instructive. There the Moscow-Conservatory-and-Juilliard-educated

Russian romantic let it all roll out, in grand gestures and dense

wall-to-wall harmonies, laying bare his admiration for classical virtuoso

Svyatoslav Richter. It's very nice, but hardly the approach to take with

this partner.

By contrast Chat Room finds Nabatov in a lighter, more playful frame of

mind, and fingers. Too wise to battle Bennink, he invites him in; the

pianist leaves the drummer plenty of room between the beats, and Han returns

the favor. Nabatov doesn't just play 'time,' in the jazz sense, but plays

kinds of time Bennink finds especially congenial: swingtime, with brushes,

as on parts of "Chat Room" or "The Lost One"; the 2/4 rhythms of early jazz,

in particular the stride-piano gait Simon gets into on "Es L�uft!";

alternating straight time and double-time on "Sorrow," set up by Nabatov's

leisurely, shuffling blues episode. (As long as they're at the jazz well,

they might as well have the whole refreshing drink.)

Fair to say that as soon as the pianist works his way into a groove, the

drummer jumps right on it, close as his shadow on the sidewalk. Simon plays

with both hands locked in rhythmic unison on "Sync"? What the heck, Han'll

join him, matching him move for move, stroke for stroke, right down to the

final note. In other contexts Bennink can be loud enough to damage a

bystander's hearing, but "Es L�uft!" for one reminds us that busy playing

needn't be deafening. He can whisper with sticks on snare too.

Oddly enough, it's the pianist who can be less suggestible, holding his

own where the challenger would have it otherwise. Listen to the way Bennink

keeps introducing short "sampled" (or sample) rhythms on "Slightly Off,"

waiting for Simon to take the bait (and while you're there, note the piano's

peculiar dreamy/driving momentum). Something similar happens midway through

"Together," where Han quietly tries to prod Simon onto a faster tempo.

But Nabatov is accommodating in other ways; he finds the trap drums

within the piano. On the opener "Chat Room" he knocks around under the hood,

on the strings and metal frame/harp, using a length of pipe, wrapped in a

thick layer of tape. ("It bounces nicely off everything," Simon says.) There

he sometimes plays different rhythms with different limbs: pipe-rattle

versus the chatter of (telegraph) keys triggering the piano's highest notes

(which Guus Janssen uses for a similar "hi-hat" effect). On "Foaming"

Nabatov places blocks of styrofoam against the strings, to change their

pitch and timbre, but listen to how metallic that special effect sounds:

rims and cymbals. And while outdoorsman Bennink likes to bring a suggestion

of the natural world into his music, stylized like everything he does, the

soft, soft birdcalls on "Prediction" are Simon's, made by raising and

lowering the keyboard lid, which he'll also drop for a cavernous bass-drum

boom.

There are a couple of (after-the-fact) homages to other pianists.

"Unperturbed" is for Paul Bley, who befriended Simon after he moved to New

York in the early '80s. "We'd hang out, taking walks through the Village,

looking in on some bands playing, and then head to the space he still kept

in the West Village, with a nice Steinway. We would play for each other and

he would say funny and often interesting things. One of those things that

can only happen in NY, I guess." The start of the Mengelberg-dedicated

"Don't Bother" resembles a raucous Han and Misha set-to, but quickly moves

toward this pair's cozier mode; Bennink tracks him gently yet again, giving

Nabatov's melodic bent free rein.

Fair to say Han gives Simon his leeway out of respect for his formidable

musical resources: not just his iron time, but his wide dynamic range,

ringing attack, mastery of the instrument's coloristic palette, and broad

historical knowledge; he covers a lot of ground, from Tchaikovsky-Scriabin

fireworks to Bartok to Tristano's or Bley's different brands of linearity,

to rumors of Monk's collapsed chords. And it's always nice to hear his

bluesy side come out; it suits him.

Nabatov's quick and precise, can go anywhere fast -- just the kind of

musician Bennink's always looking for.

No wonder Han treats him right.

Kevin Whitehead